#IndieAuth

-

#IndieAuth is a pretty neat thing, and as I'm already a big #RSS user (have been since they were in general use, just never dropped them) I guess it'd be cool to have what amounts to a way to log into various sites that I don't feel called to make single accounts for and certainly don't feel like giving access to my Gmail or Facebook.

Trouble is, I have very few places where I can put a ref="me" and a lot of the people I know don't either. Many sites don't let us edit the style sheet.

-

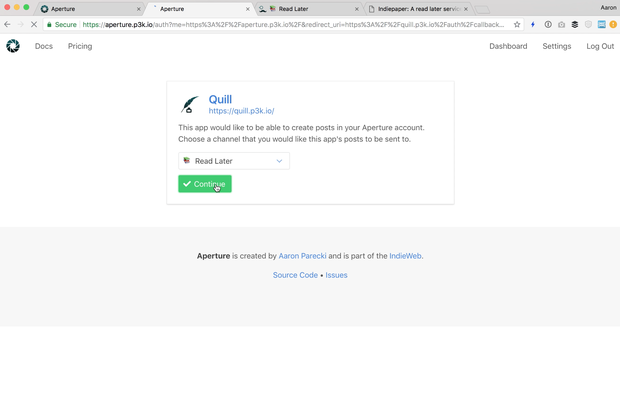

I've set up #IndieAuth on my personal site. Now on the two sites that support it I can log in using myself as an IDP.

-

-

IndieAuth: One Year Later

It's already been a year since IndieAuth was published as a W3C Note! A lot has happened in that time! There's been several new plugins and services launch support for IndieAuth, and it's even made appearances at several events around the world!continue reading...

It's already been a year since IndieAuth was published as a W3C Note! A lot has happened in that time! There's been several new plugins and services launch support for IndieAuth, and it's even made appearances at several events around the world!continue reading... -

-

-

We will be talking about 'The Many Flavors of OAuth' at @APIdaysGlobal San Francisco about #oauth2 and briefly covering identity layers #openidconnect #oidc and #IndieAuth. We have a few tickets to giveaway. Please register with code 'Soonhin' at https://www.apidays.co/sanfrancisco. See you!

-

Will be talking about 'The Many Flavors of OAuth' at https://www.apidays.co/sanfrancisco including brief overview of identity layers #openidconnect #oidc, and #IndieAuth. Use code 'Soonhin' to get free tix. @aaronpk thanks for https://aaronparecki.com/2018/07/07/7/oauth-for-the-open-web.

-

-

By golly, it's working. Here's me using Cellar Door to login to #IndieWeb's #IndieAuth page to add my implementation to the list of available implementations. ☺️ https://indieweb.org/IndieAuth#Implementations

-

OAuth for the Open Web

OAuth has become the de facto standard for authorization and authentication on the web. Nearly every company with an API used by third party developers has implemented OAuth to enable people to build apps on top of it.continue reading...

OAuth has become the de facto standard for authorization and authentication on the web. Nearly every company with an API used by third party developers has implemented OAuth to enable people to build apps on top of it.continue reading... -

-

-