Let's not overthink auth in MCP.

Yes, the MCP server is going to need its own auth server. But it's not as bad as it sounds. Let me explain.

First let's get a few pieces of terminology straight.

The confusion that's happening in the discussions I've seen so far is because the spec and diagrams show that the MCP server itself is handing authorization. That's not necessary.

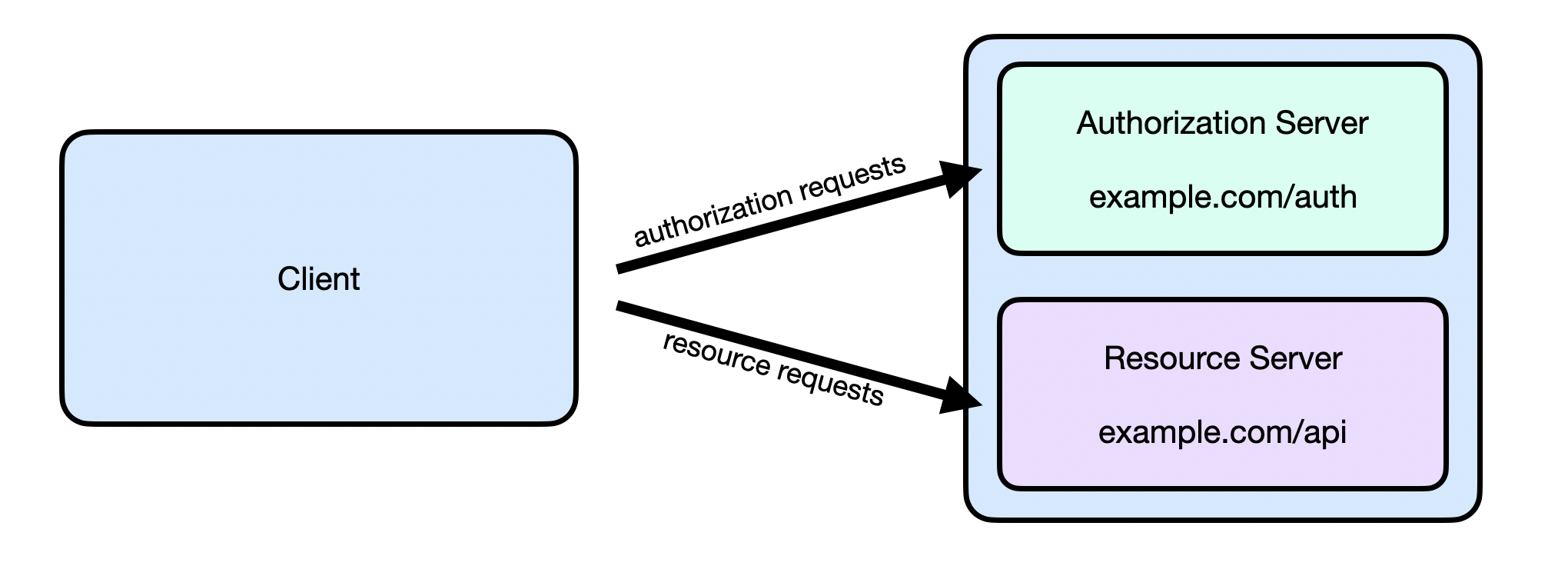

In OAuth, we talk about the "authorization server" and "resource server" as distinct roles. I like to think of the authorization server as the "token factory", that's the thing that makes the access tokens. The resource server (usually an API) needs to be able to validate the tokens created by the authorization server.

It's possible to build a single server that is both a resource server and authorization server, and in fact many OAuth systems are built that way, especially large consumer services.

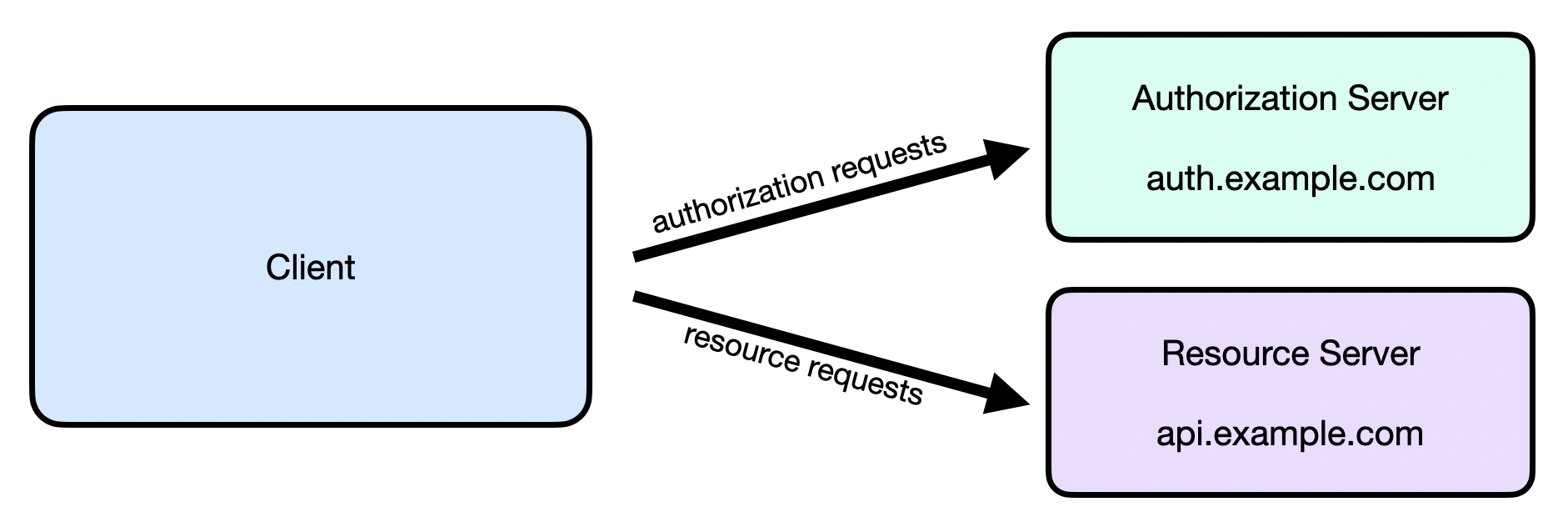

But nothing about the spec requires that the two roles are combined, it's also possible to run these as two totally unrelated services.

This flexibility that's been baked into OAuth for over a decade is what has led to the rapid adoption, as well the proliferation of open source and commercial products that provide an OAuth authorization server as a service.

So how does this relate to MCP?

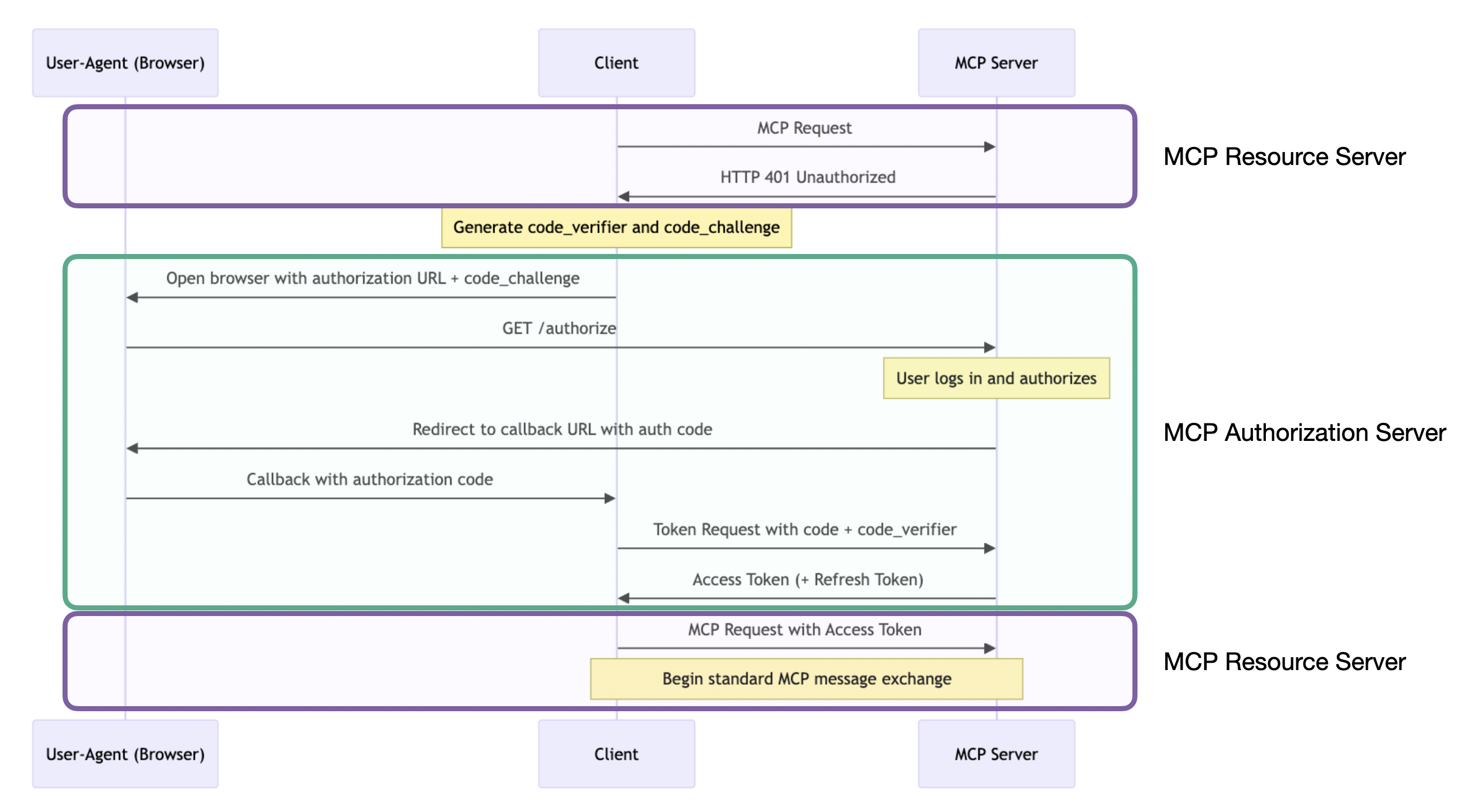

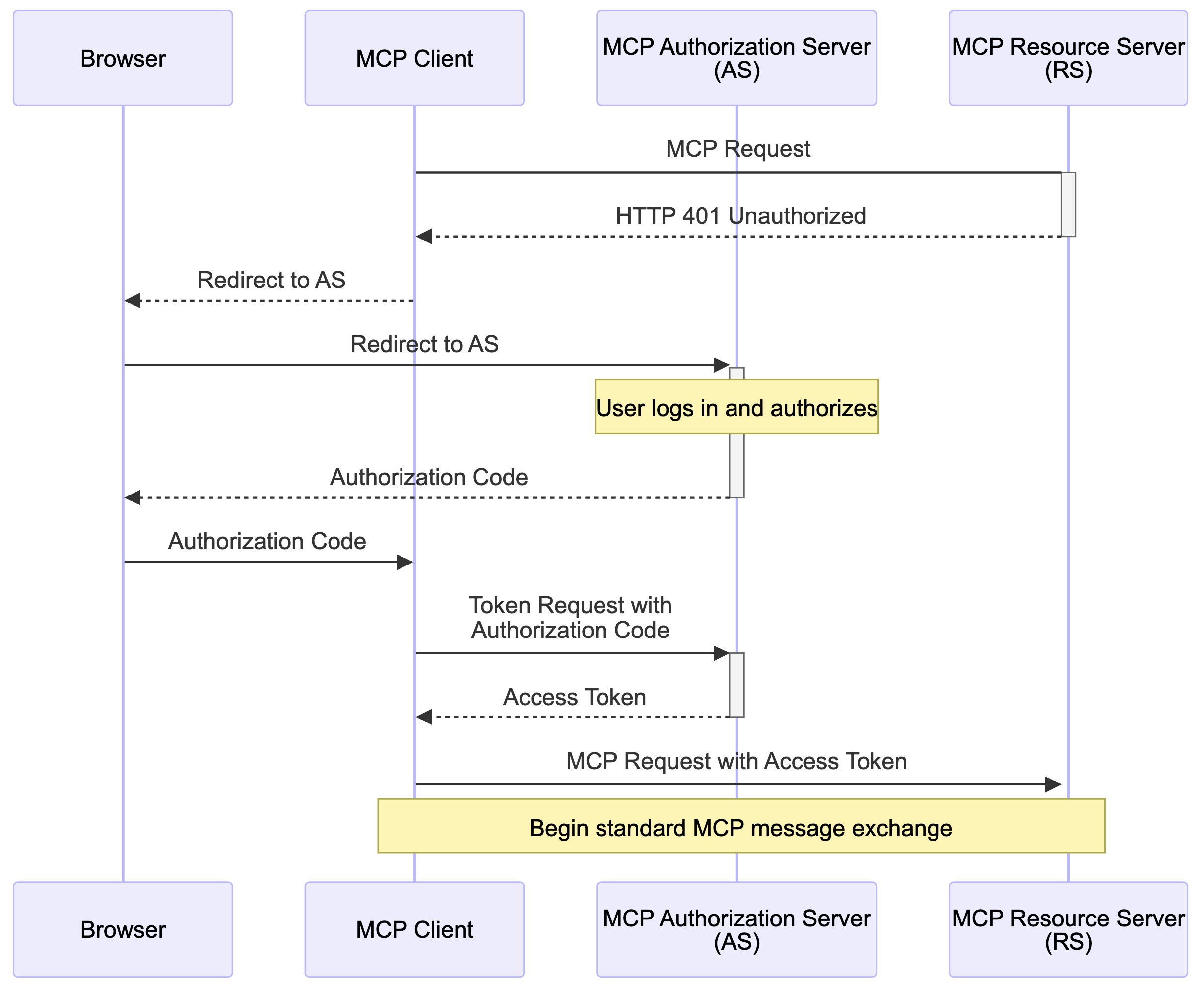

I can annotate the flow from the Model Context Protocol spec to show the parts where the client talks to the MCP Resource Server separately from where the client talks to the MCP Authorization Server.

Here is the updated sequence diagram showing communication with each role separately.

Why is it important to call out this change?

I've seen a few conversations in various places about how requiring the MCP Server to be both an authorization server and resource server is too much of a burden. But actually, very little needs to change about the spec to enable this separation of concerns that OAuth already provides.

I've also seen various suggestions of other ways to separate the authorization server from the MCP server, like delegating to an enterprise IdP and having the MCP server validate access tokens issued by the IdP. These other options also conflate the OAuth roles in an awkward way and would result in some undesirable properties or relationships between the various parties involved.

So what needs to change in the MCP spec to enable this?

Discovery

The main thing currently forcing the MCP Server to be both the authorization server and resource server is how the client does discovery.

One design goal of MCP is to enable a client to bootstrap everything it needs based on only the server URL provided. I think this is a great design goal, and luckily is something that can be achieved even when separating the roles in the way I've described.

The MCP spec currently says that clients are expected to fetch the OAuth Server Metadata (RFC8414) file from the MCP Server base URL, resulting in a URL such as:

https://example.com/.well-known/oauth-authorization-server

This ends up meaning the MCP Resource Server must also be an Authorization Server, which leads to the complications the community has encountered so far. The good news is there is an OAuth spec we can apply here instead: Protected Resource Metadata.

Protected Resource Metadata

The Protected Resource Metadata spec is used by a Resource Server to advertise metadata about itself, including which Authorization Server can be used with it. This spec is both new and old. It was started in 2016, but was never adopted by the OAuth working group until 2023, after I had presented at an IETF meeting about the need for clients to be able to bootstrap OAuth flows given an OAuth resource server. The spec is now awaiting publication as an RFC, and should get its RFC number in a couple months. (Update: This became RFC 9728 on April 23, 2025!)

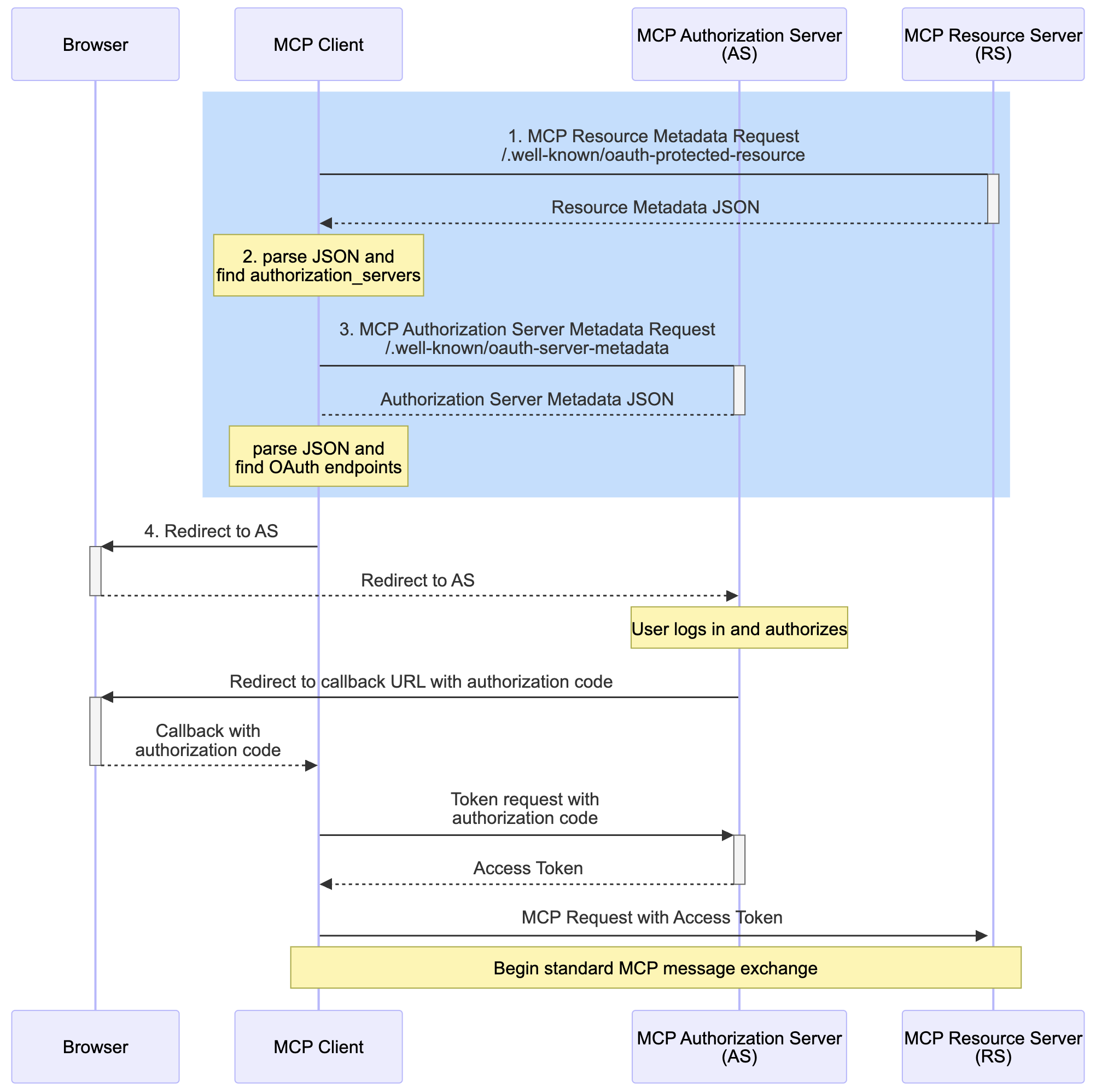

Applying this to the MCP server would result in a sequence like the following:

- The MCP Client fetches the Resource Server Metadata file by appending

/.well-known/oauth-protected-resourceto the MCP Server base URL. - The MCP Client finds the

authorization_serversproperty in the JSON response, and builds the Authorization Server Metadata URL by appending/.well-known/oauth-authorization-server - The MCP Client fetches the Authorization Server Metadata to find the endpoints it needs for the OAuth flow, the authorization endpoint and token endpoint

- The MCP Client initiates an OAuth flow and continues as normal

Note: The Protected Resource Metadata spec also supports the Resource Server returning WWW-Authenticate with a link to the resource metadata URL if you want to avoid the requirement that MCP Servers host their metadata URLs at the .well-known endpoint, it just requires an extra HTTP request to support this.

Access Token Validation

Two things to keep in mind about how the MCP Server validates access tokens with this new separation of concerns.

If you do build the MCP Authorization Server and Resource Server as part of the same system, you don't need to do anything special to validate the access tokens the Authorization Server issues. You probably already have some sort of infrastructure in place for your normal API to validate tokens issued by your Authorization Server, so nothing changes there.

If you are using an external Authorization Server, whether that's an open source product or a commercial hosted service, that product will have its own docs for how you can validate the tokens it creates. There's a good chance it already supports the standardized JWT Access Tokens described in RFC 9068, in which case you can use off-the-shelf JWT validation middleware for common frameworks.

In either case, the critical design goal here is that the MCP Authorization Server issues access tokens that only ever need to be validated by the MCP Resource Server. This is in line with the security recommendations in Section 2.3 of RFC 9700, in particular that "access tokens SHOULD be audience-restricted to a specific resource server". In other words, it would be a bad idea for the MCP Client to be issued an access token that works with both the MCP Resource Server and the service's REST API.

Why Require the MCP Server to have an Authorization Server in the first place?

Another argument I've seen is that MCP Server developers shouldn't have to build any OAuth infrastructure at all, instead they should be able to delegate all the OAuth bits to an external service.

In principle, I agree. Getting API access and authorization right is tricky, that's why there are entire companies dedicated to solving the problem.

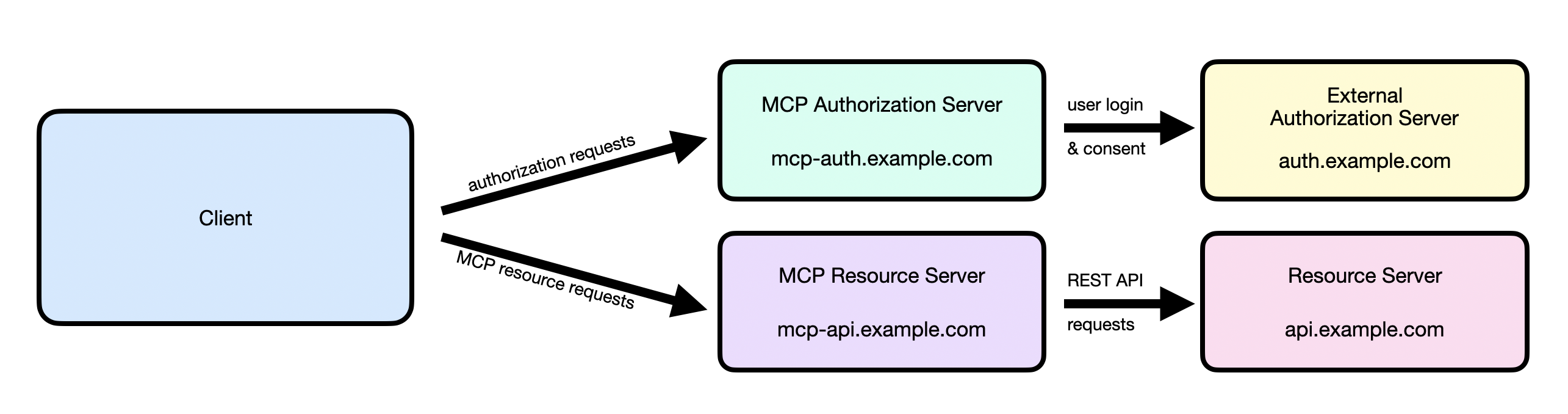

The architecture laid out above enables this exact separation of concerns. The difference between this architecture and some of the other proposals I've seen is that this cleanly separates the security boundaries so that there are minimal dependencies among the parties involved.

But, one thing I haven't seen mentioned in the discussions is that there actually is no requirement than an OAuth Authorization Server provide any UI itself.

An Authorization Server with no UI?

While it is desirable from a security perspective that the MCP Resource Server has a corresponding Authorization Server that issues access tokens for it, that Authorization Server doesn't actually need to have any UI or even any concept of user login or accounts. You can actually build an Authorization Server that delegates all user account management to an external service. You can see an example of this in PayPal's MCP server they recently launched.

PayPal's traditional API already supports OAuth, the authorization and token endpoints are:

https://www.paypal.com/signin/authorizehttps://api-m.paypal.com/v1/oauth2/token

When PayPal built their MCP server, they launched it at https://mcp.paypal.com. If you fetch the metadata for the MCP Server, you'll find the two OAuth endpoints for the MCP Authorization Server:

https://mcp.paypal.com/authorizehttps://mcp.paypal.com/token

When the MCP Client redirects the user to the authorization endpoint, the MCP server itself doesn't provide any UI. Instead, it immediately redirects the user to the real PayPal authorization endpoint which then prompts the user to log in and authorize the client.

This points to yet another benefit of architecting the MCP Authorization Server and Resource Server this way. It enables implementers to delegate the actual user management to their existing OAuth server with no changes needed to the MCP Client. The MCP Client isn't even aware that this extra redirect step was inserted in the middle. As far as the MCP Client is concerned, it has been talking to only the MCP Authorization Server. It just so happens that the MCP Authorization Server has sent the user elsewhere to actually log in.

Dynamic Client Registration

There's one more point I want to make about why having a dedicated MCP Authorization Server is helpful architecturally.

The MCP spec strongly recommends that MCP Servers (authorization servers) support Dynamic Client Registration. If MCP is successful, there will be a large number of MCP Clients talking to a large number of MCP Servers, and the user is the one deciding which combinations of clients and servers to use. This means it is not scalable to require that every MCP Client developer register their client with every MCP Server.

This is similar to the idea of using an email client with the user's chosen email server. Obviously Mozilla can't register Thunderbird with every email server out there. Instead, there needs to be a way to dynamically establish a client's identity with the OAuth server at runtime. Dynamic Client Registration is one option for how to do that.

The problem is most commercial APIs are not going to enable Dynamic Client Registration on their production servers. For example, in order to get client credentials to use the Google APIs, you need to register as a developer and then register an OAuth client after logging in. Dynamic Client Registration would allow a client to register itself without the link to the developer's account. That would mean there is no paper trail for who the client was developed by. The Dynamic Client Registration endpoint can't require authentication by definition, so is a public endpoint that can create clients, which as you can imagine opens up some potential security issues.

I do, however, think it would be reasonable to expect production services to enable Dynamic Client Registration only on the MCP's Authorization Server. This way the dynamically-registered clients wouldn't be able to use the regular REST API, but would only be able to interact with the MCP API.

Mastodon and BlueSky also have a similar problem of needing clients to show up at arbitrary authorization servers without prior coordination between the client developer and authorization server operator. I call this the "OAuth for the Open Web" problem. Mastodon used Dynamic Client Registration as their solution, and has since documented some of the issues that this creates, linked here and here.

BlueSky decided to take a different approach and instead uses an https URL as a client identifier, bypassing the need for a client registration step entirely. This has the added bonus of having at least some level of confidence of the client identity because the client identity is hosted at a domain. It would be a perfectly viable approach to use this method for MCP as well. There is a discussion on that within MCP here. This is an ongoing topic within the OAuth working group, I have a couple of drafts in progress to formalize this pattern, Client ID Metadata Document and Client ID Scheme.

Enterprise IdP Integration

Lastly, I want to touch on the idea of enabling users to log in to MCP Servers with their enterprise IdP.

When an enterprise company purchases software, they expect to be able to tie it in to their single-sign-on solution. For example, when I log in to work Slack, I enter my work email and Slack redirects me to my work IdP where I log in. This way employees don't need to have passwords with every app they use in the enterprise, they can log in to everything with the same enterprise account, and all the apps can be protected with multi-factor authentication through the IdP. This also gives the company control over which users can access which apps, as well as a way to revoke a user's access at any time.

So how does this relate to MCP?

Well, plenty of people are already trying to figure out how to let their employees safely use AI tools within the enterprise. So we need a way to let employees use their enterprise IdP to log in and authorize MCP Clients to access MCP Servers.

If you're building an MCP Server in front of an existing application that already supports enterprise Single Sign-On, then you don't need to do anything differently in the MCP Client or Server and you already have support for this. When the MCP Client redirects to the MCP Authorization Server, the MCP Authorization Server redirects to the main Authorization Server, which would then prompt the user for their company email/domain and redirect to the enterprise IdP to log in.

This brings me to yet another thing I've been seeing conflated in the discussions: user login and user authorization.

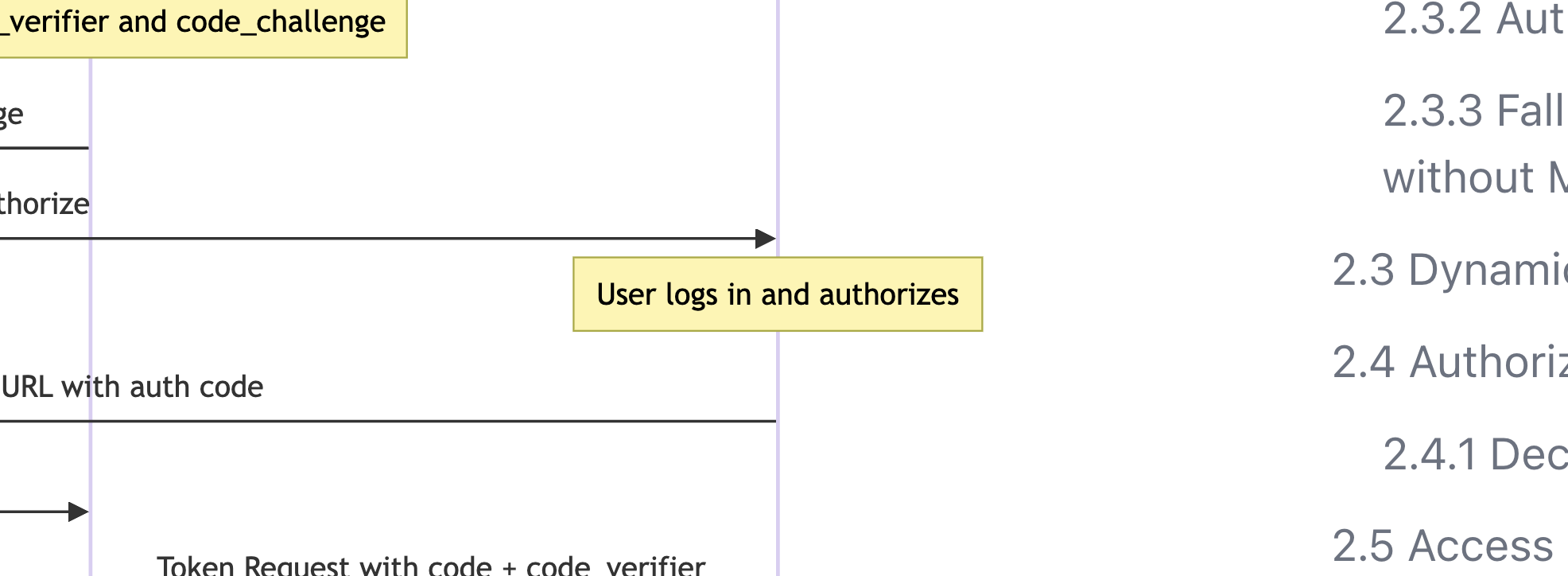

OAuth is an authorization delegation protocol. OAuth doesn't actually say anything about how users authenticate at the OAuth server, it only talks about how the user can authorize access to an application. This is actually a really great thing, because it means we can get super creative with how users authenticate.

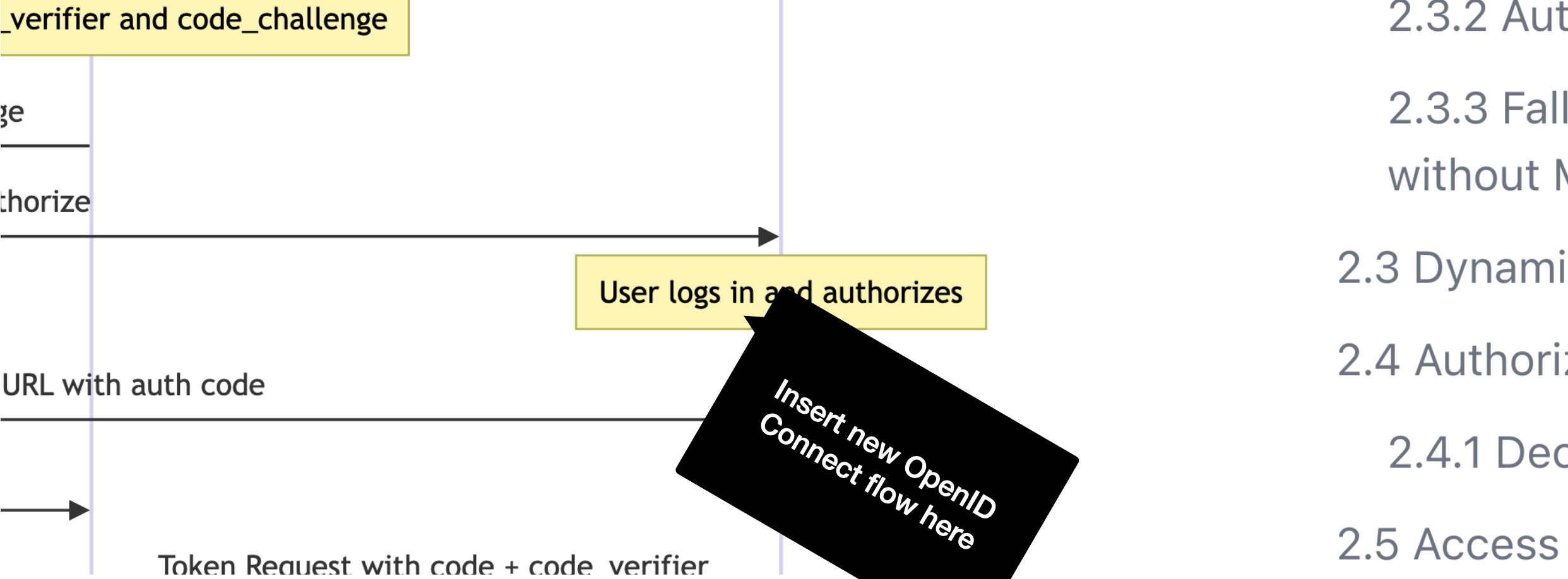

Remember the yellow box "User logs in and authorizes" from the original sequence diagram? These are actually two totally distinct steps. The OAuth authorization server is responsible for getting the user to log in somehow, but there's no requirement that how the user logs in is with a username/password. This is where we can insert a single-sign-on flow to an enterprise IdP, or really anything you can imagine.

So think of this as two separate boxes: "user logs in", and "user authorizes". Then, we can replace the "user logs in" box with an entirely new OpenID Connect flow out to the enterprise IdP to log the user in, and after they are logged in they can authorize the client.

I'll spare you the complete expanded sequence diagram, since it looks a lot more complicated than it actually is. But I again want to stress that this is nothing new, this is already how things are commonly done today.

This all just becomes cleaner to understand when you separate the MCP Authorization Server from the MCP Resource Server.

We can push all the complexity of user login, token minting, and more onto the MCP Authorization Server, keeping the MCP Resource Server free to do the much simpler task of validating access tokens and serving resources.

Future Improvements of Enterprise IdP Integration

There are two things I want to call out about how enterprise IdP integration could be improved. Both of these are entire topics on their own, so I will only touch on the problems and link out to other places where work is happening to solve them.

There are two points of friction with the current state of enterprise login for SaaS apps.

- IdP discovery

- User consent

IdP Discovery

When a user logs in to a SaaS app, they need to tell the app how to find their enterprise IdP. This is commonly done by either asking the user to enter their work email, or asking the user to enter their tenant URL at the service.

Neither of these is really a great user experience. It would be a lot better if the browser already knew which enterprise IdP the user should be sent to. This is one of my goals with the work happening in FedCM. With this new browser API, the browser can mediate the login, telling the SaaS app which enterprise IdP to use automatically only needing the user to click their account icon rather than type anything in.

User Consent

Another point of friction in the enterprise happens when a user starts connecting multiple applications to each other within the company. For example, if you drop in a Google Docs link into Slack, Slack will prompt you to connect your Google account to preview the link. Multiply this by N number of applications that can preview links, and M number of applications you might drop links to, and you end up sending the user through a huge number of OAuth consent flows.

The problem is only made worse with the explosion of AI tools. Every AI tool will need access to data in every other application in the enterprise. That is a lot of OAuth consent flows for the user to manage. Plus, the user shouldn't really be the one granting consent for Slack to access the company Google Docs account anyway. That consent should ideally be managed by the enterprise IT admin.

What we actually need is a way to enable the IT admin to grant consent for apps to talk to each other company-wide, removing the need for users to be sent through an OAuth flow at all.

This is the basis of another OAuth spec I've been working on, the Identity Assertion Authorization Grant.

The same problem applies to MCP Servers, and with the separation of concerns laid out above, it becomes straightforward to add this extension to move the consent to the enterprise and streamline the user experience.

Get in touch!

If these sound like interesting problems, please get in touch! You can find me on LinkedIn or reach me via email at aaron@parecki.com.